How can we rationalise grotesque art in contemporary China?

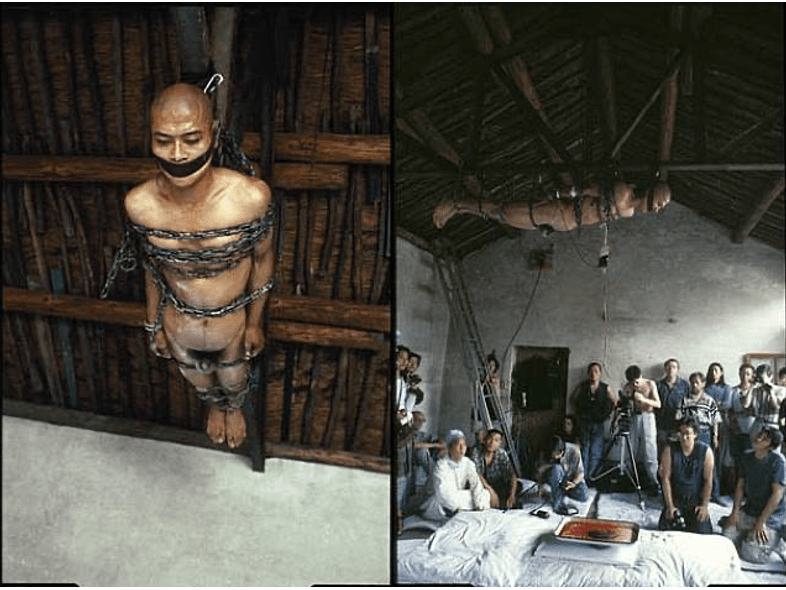

Contemporary Chinese grotesque art, exemplified by works such as Zhang Huan’s 65kg, Zhu Yu’s Eating People, and Qin Ga’s Bingdong Freeze serves as a profound commentary on the human condition, societal norms, and the boundaries of artistic expression. These provocative pieces employ extreme and often shocking imagery to challenge viewers’ perceptions and provoke emotional and intellectual reactions. In a rapidly transforming China, where traditional values collide with modernity and economic growth, these artists use grotesque elements to explore themes of vulnerability, mortality, and ethical limits. By doing so, they not only push the boundaries of what is considered acceptable in art but also force audiences to confront uncomfortable truths about human suffering, political repression, and the commodification of life. This essay examines how these artworks disrupt conventional aesthetic norms and highlight the interplay between artistic freedom and societal expectations. This essay has a repeated use of the word force. I felt it necessary to use this word as it directly parallels how I felt when I first engaged with these works. I felt forced to feel uncomfortable and it was involuntary for me to engage with the question of why these artists felt compelled to go to these extreme lengths. In addition to this I have chosen to only include the image of 65kg as it is solely the artist himself involved in the piece. The two other works involve the use of an external body and whether real or fake, the inclusion of an image of their naked bodies felt like a violation of their agency.

The grotesque nature of 65kg is evident in the extreme physical conditions Zhang subjected himself to. The naked and suspended body, contorted and visibly strained, evokes a strong sense of discomfort and unease. This feeling is enhanced further when the viewers walk into the space to smell his blood and sweat burning in the pan below.[1] This deliberate use of grotesque imagery serves to push the boundaries of what is traditionally considered acceptable in art, forcing viewers to confront raw voluntary human suffering. While Zhang himself states that he cannot stop political interpretations of his works, he argues that there are no political motivations behind them.[2] However, it can be argued that Zhang’s self-imposed suffering becomes a powerful metaphor for the broader societal and personal struggles faced by individuals in times of great change and uncertainty. This is reinforced by the fact that he said that his upbring in the poor province of Henan where he was constantly surrounding by death by disease and death by abortion resulted in his turn against classical art to more performative and experimental art, therefore 65kg can be interpreted as a critique of the oppressive socio-political environment in China during the early 1990s.[3] The bound, naked body symbolises the lack of freedom and autonomy experienced by many under an authoritarian regime and the legacy of the Cultural Revolution. Zhang states that the performance delves into existential questions about human existence, pain, and endurance. By pushing his body to its limits, he prompts viewers to consider the nature of suffering and the human condition. The grotesque elements of the performance underscore the harsh realities of life and the inescapable aspects of physical and emotional pain. We can see a rationalisation of this grotesque as it serves to disrupt conventional aesthetic norms and catalyse contemplation of the harsh realities that Zhang was experiencing. The raw and unfiltered presentation of suffering and endurance challenges the viewer to confront uncomfortable truths about why artists such as Zhang feel compelled to put their body through this sort of human experience which is such a stark difference from traditional Chinese art.

Eating People is a performance art piece that purportedly depicts Zhu Yu consuming a human foetus. The artwork includes photographs documenting the act, creating a profound sense of shock and revulsion. Zhu Yu presented this work as part of the “Bu hezuo fangshi” exhibition in Shanghai in November 2000, sparking immediate outrage and intense debate. The grotesque nature of Eating People is evident in its explicit and visceral content. The depiction of cannibalism which is already a taboo subject evokes strong feelings of disgust and horror. This deliberate use of grotesque imagery is intended to evoke a visceral reaction from the audience, forcing them to confront the boundaries of morality, legality, and human decadency. The primary aim of Zhu Yu’s work appears to be the provocation of moral outrage and the questioning of ethical boundaries. By simulating an act as taboo as cannibalism, Zhu Yu confronts the viewer with the extremities of human behaviour, challenging them to reconsider their own moral frameworks. It could be argued for example that Eating People serves as a critique of extreme consumerism and the commodification of human life. In a rapidly modernising China, the relentless pursuit of economic growth has led to significant social and ethical dilemmas. The artwork can be seen as a metaphor for the ways in which humanity can be consumed by its own material desires.

Zhu Yu’s piece also comments on the nature of contemporary art itself, pushing the boundaries of what is considered acceptable and questioning the role of shock value in art. By crossing these lines, Zhu Yu invites a discussion about the limits of artistic freedom and the responsibilities of artists. The artwork provoked widespread outrage both in China and internationally. This was exacerbated my technologically and social media where the images were spread without captions leading the piece to be easily misread and fabricated. This piece further raised significant ethical and legal questions about the limits of artistic expression. Many critics condemned the piece as morally reprehensible, while others defended it as a legitimate form of artistic provocation. The Chinese government swiftly condemned the artwork, and it was banned from public exhibition. Zhu Yu faced intense scrutiny, and the controversy highlighted the tensions between artistic freedom and state censorship in China. This piece became a focal point for discussions about the role of art in society and the responsibilities of artists to their audience.

Similar questions regarding the ethics of art are reinforced by Bingdong Freeze. This piece is a performance and installation piece that involved the use of an adolescent female cadaver. The work was part of a broader exhibition known for its provocative and boundary-pushing content. The exhibition, held in Shanghai, aimed to explore themes of injury, pain, and the human condition through extreme and often grotesque imagery. The grotesque nature of Bingdong Freeze is immediately apparent in its use of a human cadaver. This choice evokes again a strong reaction of shock and discomfort. The cadaver is not only a symbol of death but also an object that challenges societal taboos surrounding the treatment and representation of the people who suffered from AIDS.[4] The use of an adolescent female body further intensifies the emotional impact, as it confronts issues of vulnerability and innocence.

Furthermore, central to Bingdong Freeze is the theme of mortality. By presenting a human cadaver in an art context, Qin Ga forces viewers to confront the reality of death and the impermanence of life. This stark portrayal serves as a reminder of the inevitable decay and fragility of the human body. The artwork raises critical questions about the objectification and dehumanisation of the human body. By using a cadaver as an artistic medium, Qin Ga comments on the ways in which bodies can be reduced to objects, stripped of their humanity and individuality. This theme resonates with broader societal issues related to the commodification and exploitation of human beings. We also see this through John Duncan’s Blind date. The performance consisted of Duncan purchasing a cadaver from a medical school in Tijuana, Mexico. He then engaged in sexual intercourse with the cadaver, which was later cremated. Duncan recorded the event on audio tape and used these recordings as part of the performance, presenting them as part of an exhibition. It is interesting to note that Meiling Cheng states that both Eating People and Blind Date involve a male exerting his living will on a dead other who has no power to resist his invasion. In addition to this both artworks subsist on the tenuous membrane between aggressive art and legally liable criminal acts. Bingdong Freeze challenges cultural and ethical boundaries regarding the treatment of the dead. This boundary-pushing approach forces viewers to reconsider their own cultural and ethical beliefs about death and the human body.

In conclusion, the rationalisation of grotesque art in contemporary China can be understood through its capacity to serve as a profound commentary on the human condition, societal norms, and the boundaries of artistic expression. The works of Zhang Huan, Zhu Yu, and Qin Ga, through their use of extreme and often shocking imagery, push the boundaries of what is considered acceptable in art, compelling audiences to confront uncomfortable truths about human suffering. These artists utilise grotesque elements not merely for shock value but to provoke deep emotional and intellectual reactions, encouraging viewers to engage in critical reflection on the darker aspects of human existence.

Bibliography

Cheng, M. (2013). Beijing Xingwei: contemporary Chinese time-based art. London: Seagull.

Hung, W., & Art, D. a. (1999). Transience: Chinese experimental art at the end of the twentieth century. Chicago: David and Alfred Smart Museum of Art, University of Chicago.

Zhijian, Q. (2014). Performing Bodies: Zhang Huan, Ma Liuming, and Performance Art in China. Art Journal , Pages 60-81.

[1] Zhijian, Q. (2014). Performing Bodies: Zhang Huan, Ma Liuming, and Performance Art in China. Art Journal , Pages 60-81.

[2] Zhijian, Q. (2014). Performing Bodies: Zhang Huan, Ma Liuming, and Performance Art in China. Art Journal , Pages 60-81.

[3] Hung, W., & Art, D. a. (1999). Transience: Chinese experimental art at the end of the twentieth century. Chicago: David and Alfred Smart Museum of Art, University of Chicago.

[4] Cheng, M. (2013). Beijing Xingwei: contemporary Chinese time-based art. London: Seagull.