Modernisation and Westernisation in Asian Art

The evolution of Asian art reflects an interplay of influences, where traditional practices intersect with modernisation and Westernisation. Modernisation encompasses a multifaceted process of embracing new technologies, ideas, and social structures to adapt to evolving circumstances and enhance societal well-being. This is reinforced by Gilbert Rozman’s definition of modernisation in his work The Modernization of China where he states, “we view modernization as the process by which societies have been and are being transformed under the impact of the scientific and technological revolution”.[1] In Asian art, modernisation manifests through the adoption of innovative artistic techniques, materials, and subjects. It entails a shift in artistic practices and institutions to reflect contemporary values and address social concerns while preserving original artistic forms and expressions.

Westernisation on the other hand, indicate the assimilation of Western cultural practices and aesthetics, often under the influence of colonialism, globalisation, or cultural imperialism. In the realm of Asian art, Westernisation entails the direct imitation of Western artistic styles and techniques, sometimes overshadowing original artistic traditions. This adoption of Western norms can be driven by a desire to conform to Western aesthetic standards, gain recognition in Western art markets, or assert cultural superiority over indigenous practices. This essay aims to explore the nuanced distinction between modernisation and westernisation in the context of Asian art, by looking at cultural identity and representation and the agency of the Asian art world. This essay will further look at scholars such as Hellen Burnham, Karatani Kōjin, John Clark and Shūji Takashina to support these viewpoints.

Bibliography

Rozman, G. (1981). The Modenization of China. New York: The Free Press.

Burnham, H. (2014). “The Allure of Japan,” . In H. Burnham, Looking East: Western Artists and the Allure of Japan (pp. 12-27). Boston: Museum of Fine Arts,.

Sakamoto, H. (2004). The Cult of “Love and Eugenics” In May Fourth Movement Discourse. Positions, 329–376.

Clark, J. (1993). “Open and Closed Discourses of Modernity in Asian Art,”. In J. Clark, Modernity in Asian Art (pp. 1–17). Honolulu:: University of Hawaii Press,.

Karatani Kōjin. (1994). Japan as Museum: Okakura Tenshin and Ernest Fenollosa,. In A. Munroe, Japanese Art after 1945: Scream Against the Sky (pp. 33–39). New York : Harry Abrams.

Greenberg, C. (1965). Modernist Painting,” Art and Literature . In F. a. Frascina, Modern Art and Modernism : A Critical Anthology (pp. 5 -10). Taylor & Francis Group.

Takashina, S. (1987). Shūji Takashina“Eastern and Western Dynamics in the Development of Western-Style Oil Painting during the Meiji Era,”. In J. T. Gerald D. Bolas, Paris in Japan: The Japanese encounter with European painting (pp. 20–31). Washington: Washington University .

Click Here To Find Full Commentary

Cultural Revolution – A Break From The Past?

The Cultural Revolution in Mao’s era was a clear break away from the past. The cultural revolution launched in 1966 aimed to purge Chinese society of bourgeois elements and promote proletarian culture. Mao encouraged the creation of revolutionary art that glorified the Communist party, the working class, and the ideals of the revolution and this led to the proliferations of art forms such as propaganda posters. This essay will highlight how the purpose of these posters was to further promote Mao and the Chinese Communist party throughout society. Mao understood that art could be politicised and spread throughout society in order to spread his ideology and doctrine in a way that seemed uncoerced and nonviolent. This is supported by his notion of the purpose of art. Mao stated in his 1942 lectures that “there is no such thing as art for art’s sake”[1] and that a political criterion was primary while an aesthetic criterion was secondary. This essay will argue that while the Cultural Revolution itself had a drastic impact on the traditional Chinese culture that existed in the past, it will also recognise that this cultural shift was not unexpected and had been growing since the communist takeover in 1949.

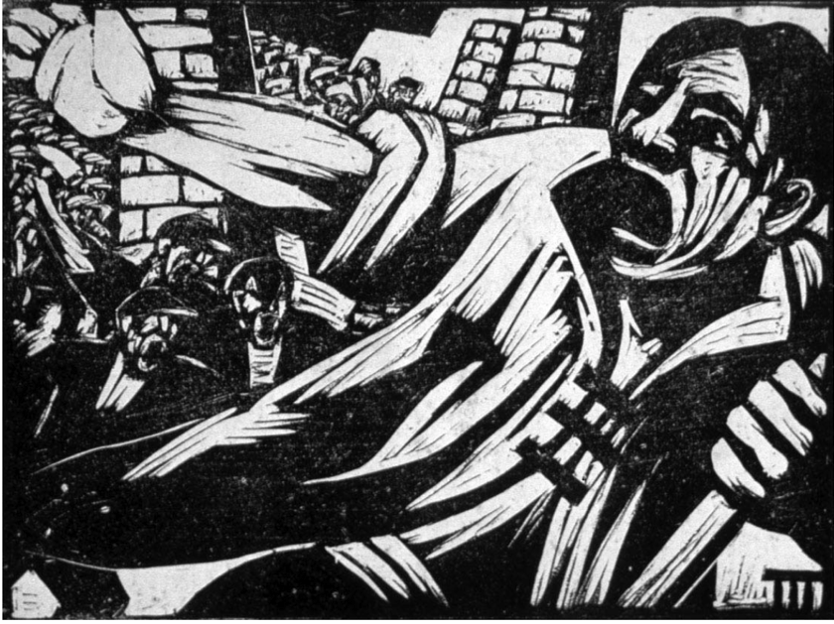

Hu Yichuan, To the Front!, woodcut, 1932, 9 1/8 X 12.” Lu Xun Memorial, Shanghai.x

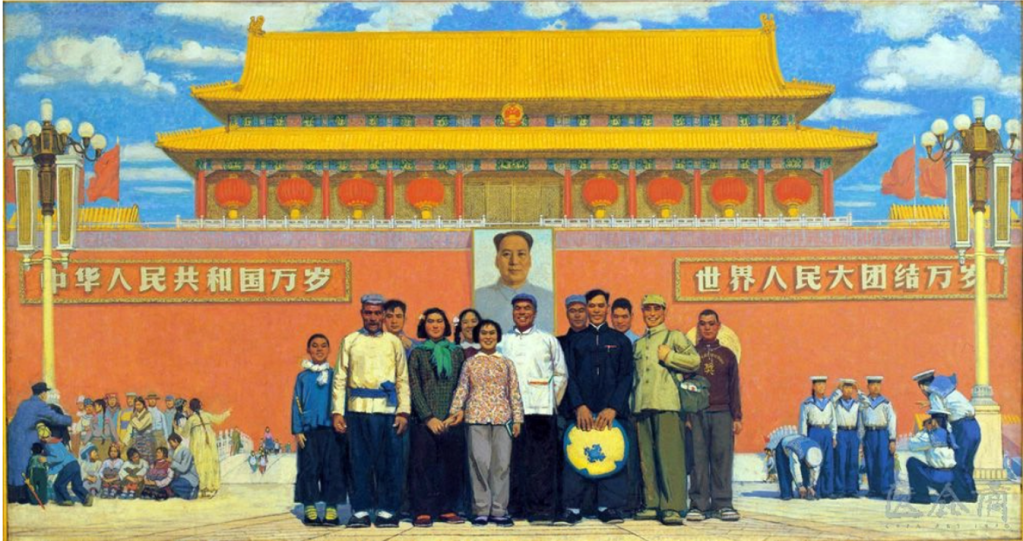

Sun Zixi, In Front of Tiananmen, 1964. oil on canvas, 153 x 294 cm. National Art Museum of China, Beijing.

Dong Xiwen, The Founding of the Nation, 1953, copied by Jin Shangyi and Zhao Yu in 1972, and modified by Yan Zhenduo and Ye Welin in 1979, oil on canvas, 230 x 402 cm (National Museum of China, Beijing)

Bibliography

Wong, P. P. (1997). Propaganda Posters from the Chinese Cultural Revolution. The Historian, 777–794.

Tse-tung, S. w. (1967). Zedong Mao. Foreign Languages Press : Perking.

Evans, H., & Donald, S. (1999). Introducing Posters of China’s Cultural Revolution. In H. Evans, & S. Donald, Picturing power in the People’s Republic of China: posters of the Cultural Revolution (pp. 1-127). Oxford : Rowman & Littlefield Publsihers.

Benewick, R. (1999). “Icons of Power: Mao Zedong and the Cultural Revolution,. In H. Evans, & S. Donald, Picturing power in the People’s Republic of China: posters of the Cultural Revolution (pp. 123-137). Oxford: Rowman & Littlefield Publisher .