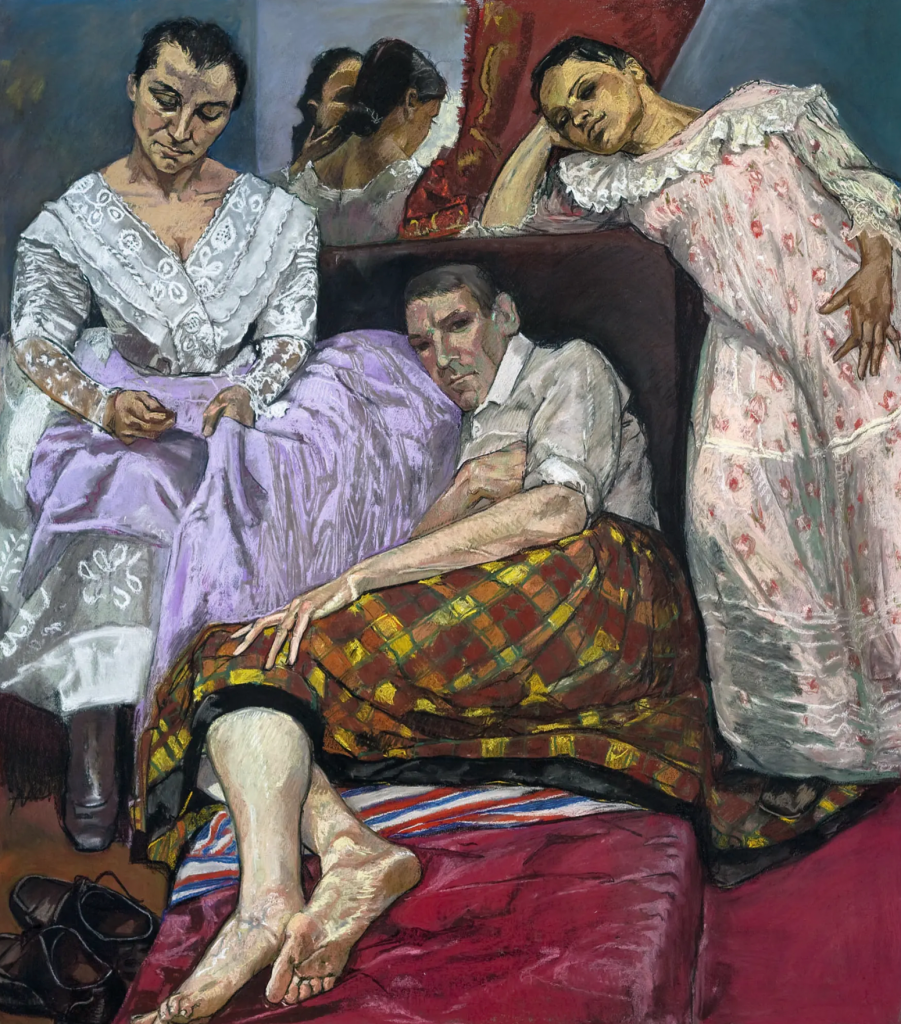

‘The Company of Women’ is part of a 1997 series entitled ‘Father Amaro’ by the Portuguese artist Paula Rego. Based on the novel, ‘The Crime of Father Amaro’ written by Eca De Queiros in 1875, Rego conveys the long-lasting effects of childhood whilst brutally ridiculing the hypocrisy of the Roman Catholic Church. Anthony Rudolf who posed for the figure of Amaro, the main character within the novel, reflects these two narratives which simultaneously exist within the piece.

Anthony immediately draws the viewers’ attention due to his elongated limbs, angular positioning, and narrow feet. His pale legs just off the centre of the composition against the disturbed burgundy sheets, accentuates his presence. Embedded between the two women beside him, he appears comfortable and “cosy”. This is corroborated by the way Anthony is leaning against the women’s skirt and angled towards her, relying on her for protection from the spectators’ opinions. Amaro too felt comfort when surrounded by women as his childhood consisted of maids constantly “encouraging him to nestle amongst them and smother him in kisses”. Anthony’s direct gaze combined with the large-scale piece, viscerally communicates the feeling of comfort and awareness that he is being watched by the viewer.

Displaying the dirty red and yellow patterned material covering Anthony as either a skirt or a blanket, evokes a sense of ambiguity. As a skirt, it may align with the femininity that Amaro was immersed in as a child as “the maids feminised him and dressed him up as a woman.”. However, his large facial features and oversized feet pervade this fragile, powerless demeanour and displace it with a grown masculine presence. This battle between his internal femininity, and the external obligation to be masculine culminates into Anthony’s juxtaposing attire of wearing both a skirt and a shirt. Although, this outgrown portrayal may allude to an attachment to his childhood and the comfort, and uncomplicated ease of the smothering attention given to him. Desire for comfort is symbolised through his rolled-up sleeves and the leather brown worn shoes that are neatly placed to the left of the bed. Through entering this room, he relinquishes his masculine façade and adopts the condition he is most comfortable in.

While this interpretation is supported by Paula Rego saying that “he’s imagining what it would be like to be dressed as a woman”, it is undeniable that there are darker connotations of the clandestine and blasphemous relationship between Amaro and Amelia, his secret love interest who is outwardly betrothed to a clerk. If we consider the material that covers Anthony as a blanket, this significantly changes the narrative of the scene. Openly displaying his calves and feet, we can assume that the rest of his lower body is exposed under the blanket, reflecting the sexual encounters. With Amelia leaning on the bed this further alludes to the idea that sexual misconduct is their underlying connection.

Between 1928 and 1968 Portugal was under the repressive dictatorship of Salazar. He promoted the ‘Fatima’, a catholic shrine in central Portugal. With Anthony placed within the centre of the composition, he symbolises this central importance of Catholicism within Portugal. Rego mocks this Catholic foundation to Portuguese society as the Roman Catholic Church is riddled with hypocrisy. The mockery is amplified as Amelia, who has had an affair, takes the shape of the Virgin Mary within the novel, a woman who epitomises what it means to practise not only celibacy but dedication to one entity, God. This exacerbates the disparity between what should be the true nature of the Catholic Church and the reality of it.

Despite Amelia not being subject to sexual coercion, exhibited through her partially lustful gaze, the dark shadows around her eyes combined with her stoic expression evokes a sense of resentment. Within all versions of the novel, she ends with an eradication from the storyline, while Amaro can restart his life, almost performing absolution on himself. This mirrors the constant dismissal of corrupt priesthood, allowing them to exploit their indestructible power. However, Paula Rego reverses this power dynamic. Anthony is physically on a lower level compared to the other women within the composition. This in combination with Amelia’s continued presence within the rest of the ‘Father Amaro’ while Amaro diminishes, highlights how Amelia is the strong survivor.

The novel itself was a favourite of Rego’s fathers. His anticlericalism motivated her to rebel against the constructs built within Portugal through her work. The way in which the suppressive dictatorship silenced herself and her father, much like the way the corruption within the church muzzled the victims of abuse, Paula Rego necessarily unearths the continued dishonesty within the church, something Portugal struggled to address.